It was my mother in law’s birthday yesterday, and a very sad thing not to be able to call and sing to her anymore, or send her flowers.

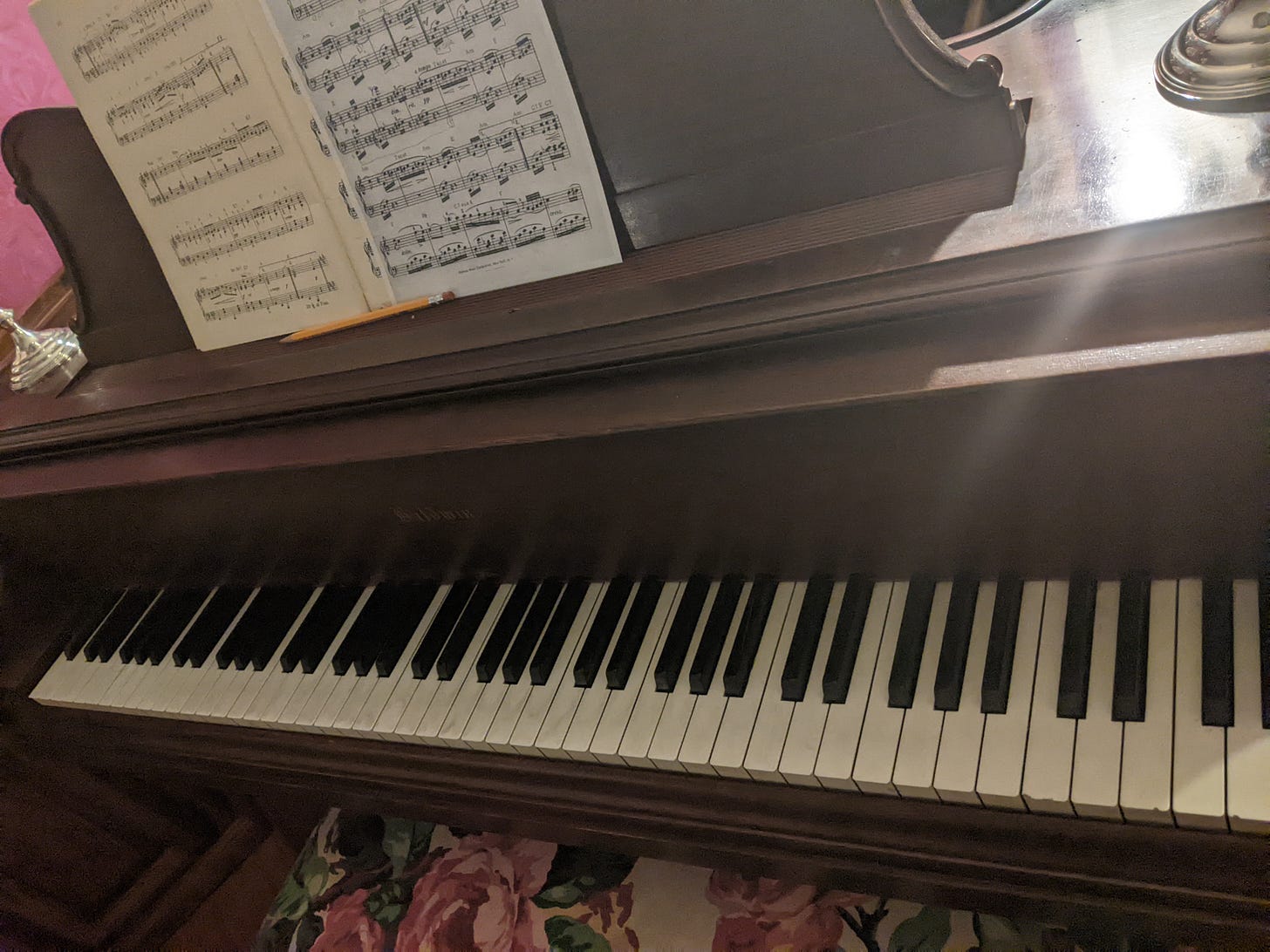

I had a piano lesson instead, on her beautiful Baldwin, the one her mother bought for her as a teenager when her father died. The receipt is still in the piano bench for $2828, financed like a car and paid for in installments. A lot of money in 1951. Priceless, now.

I remember sitting on this bench when we visited Colorado, my son and I laughing at the steampunk sounding title of the book on the music rack above the ivories: Czerny’s School of Velocity. It had a lot of notes in it, for playing really really fast. It was one of her favorites.

We never heard her play.

Apparently she was very good. You would imagine so, having a place to focus when she missed her dad. But she was a modest person. She played for herself, not to perform. Whenever we were around she was in hosting mode.

I’ve got a place to put my feelings now when I miss my dad. His birthday was a week ago. Both of them passed away in 2022.

My piano teacher, the extraordinary Daniel Finnamore in a tweed suit, marked up the sheet music for Für Elise. He showed me where to use the pedal and laid down some next-level piano nerdery about Beethoven’s Un Cordo that made me feel like a worthy student. It meant a lot to me. I’ve got some worthiness issues with this song.

I used to have it memorized. I don't know where that confidence went. The notes feel foreign under my fingers and I don’t know how I ever read the treble clef. I taught myself to play this song as a teenager. For my dad.

Because he said he would give me twenty five bucks if I did.

I'm sure he didn't expect me to take him up on that. After all, I was unmotivated and lazy as far as he was concerned, only interested in horses and books. And then there was that boyfriend he’d heard I was holding hands with in school hallways. Nothing good could come of that.

But I learned the iconic song, inspired by its yearning beauty, its calling out from the soul, its complicated fingerwork cascading down the high notes and the thunder sang from the depths. Finally I was ready. I sat Daddy down to listen. “Make yourself comfortable on the couch.” He did so with a happy sigh…and opened the newspaper.

When I was done, I turned around to seek the marvel on his face but it was behind the paper. “Hey,” I shouted, “Well?”

“Beautiful,” he mumbled, absent-mindedly.

I was beginning to turn red. “That will be $25 please!” Now it was his turn to blush. Or it should have been. But he had no shame. He flipped the paper down and glanced at the piano.

“What, you played from memory?”

“Yes,” I said proudly.

“But what I wanted was for you to play it while you were reading the music,” he said. I loved him but boy could my dad be a jerk sometimes. I slammed the piano shut and stomped off to my room.

“Krissy, don’t be like that,” he called after me.

I confronted him years later when my son was taking piano lessons. Becoming a mom had taught me how to see good and bad behavior clearly, had taught me how to scold effectively. And I had been practicing how to confront him about it.

“You still owe me twenty five bucks,” I said over pasta with mizithra cheese at the Old Spaghetti Factory. He looked confused. I told him the story.

“Oh, that,” he said. “I didn’t quite know how to handle my feelings just then. What I wanted was for you to learn to play the piano for it's own sake, for the love of learning and the beauty of music.” I was not unmoved.

“Well, I definitely get that,” I said. “I got that. But still, you broke your word.” My son slurped his sauce, taking this all in.

“I’m sorry, Krissy.” He took my hand and kissed it. I got a little weepy. It had taken me twenty years to get the apology I so needed and deserved.

“Well,” I said, “it's not too late to make good on your word.” I withdrew my hand and turned it palm up. I had him dead to rights. He gave a funny, high laugh, took some bills out of his wallet, and tossed it towards me with a funny frown on his face. “Bravo, Daddy, better late than never.” I kissed him to show him he was forgiven. Then I said, “I will put this towards your grandson’s first piano lesson.”

Years later, I added up the cost of Under The Sea, which my son played at his recital. At $35 per lesson over two years, it had cost me the price of his grandma’s piano. But by the time he got to middle school, the kid was able to sit down with sheet music and engage his fingers with the musical mind of Miles Davis. We sent both grandma and grandpa videos of the jazz band performance.

It’s just as well neither of them can hear me struggle through this old Beethoven piece today. Time has slowed my fingers and brains down, but grief has made me able to focus on music again. I play the first few bars again and again until I feel better. Art is worth investing practice, attention, and money in, if only for the way it helps us handle the velocity of life.

Such a sweet story - thank you!!